A visual essay by Friederike Heyne and Henrike Louise Hoffmann

I. Introduction

The seminar “Single in the City: Gender, Media and Urban Space” investigated new gendered subjectivities in urban areas with a focus on Asia, particularly India and China, that have emerged due to changing family patterns and various transcultural encounters such as border-crossing media, migration flows, cosmopolitan aspirations and neoliberal notions of ‘Global cities’. A topic that has not yet been touched upon in the seminar due to its non-Asian location is the role of urban African women in this context. Shortly after the session on media representation of singlehood, an article about a new African web series called ‘An African City’ appeared in Henrike’s Facebook timeline and after a first glance, we both eagerly started to watch the episodes of its first season that luckily were available for free on YouTube. The series is not only entertaining, but an outstanding case study of the representation of single women in urban spaces in Africa with the help of social media. It shows a picture that is most likely unknown to many outside of Africa. According to Pim Higginson the idea of African popular culture is still representing a challenge as the discourse is highly influenced with post colonialism and the corresponding idea that culture can be divided into an inside and outside[1]. Such preconceived ideas make it difficult for new and accurate depictions of African topics, which is why ‘An African City’ can contribute such an enormous part to this discussion[2].

By writing about an African web series, we hope to further our transcultural perspective, which most often concentrates on Asia and Europe in a global context. The (new to us) topic of ‘Afropolitans’ and the idea to present the world with a new narrative about African women, away from stereotypes of poverty and HIV, is one that we consider fitting to the context of the HERA project in which this seminar is placed. Moreover, it seems very likely to us that the depiction of women in the series is not much different from women in other series all across the world.

With this paper we analyse how single African women are framed in the series, according to various factors that determine the lives of single women all over the world. In order to do so, we will give a short introduction to the series in Chapter II, looking at its plot, its production and the response. Chapter III then analyses the different ways single women are framed in the series. Hard factors cover questions of structural settings, such as politics and financial independence whereas soft factors look into social components such as beauty, fashion, love and the issues that come with being a repatriate. We summarise our conclusions in Chapter IV.

II. The Series

‘An African City’ is an African web series that was first broadcast in 2014. In order to understand how the series frames young single African women, this chapter provides an understanding of the basic plot and the circumstances of its conceptualisation and production, before we go on to analyse the individual factors that play into that framing in the following chapters.

1. The Plot

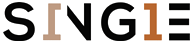

Loosely modelled upon the framework of the famous series ‘Sex and the City’, ‘An African City’ follows the lives of five “single and fabulous” women of the upper middle class in Accra, Ghana. They fall into a category defined as ‘Afropolitans’ by Taiye Selasi in her short essay “Bye-Bye Barbar”[3]: They are the children of African emigrants who grew up in various places throughout the world, in an age of globalization and the increasing hybridity of cultural identity. Afropolitans are often well-educated, aware and always renegotiating their Africanness in relation to their current position, and eager to change the global perception of Africa as underdeveloped ‘country’ towards an appropriate perspective that understands the complexity and the challenges of the African continent and its people. The five protagonists of ‘An African City’ come from various African countries and grew up in either the United States or the UK, where they also graduated from high rank universities. In the setting of the series all of them have recently moved back to Accra to pursue new career paths. On the series’ website each character is given a short introduction, highlighting their multicultural upbringing, their first class education and some defining character traits:

Illustration 1: Presentation of the Characters on the website of the series (source: http://anafricancity.tv)

Similar to the protagonists of ‘Sex and the City’, the narrator, Nana Yaa, is a young writer (the Carrie equivalent), whose friends include a rather naïve catholic (Charlotte in ‘Sex and the City’), a sexually open and experienced marketing agent with a quick wit (in adaptation of Samantha in ‘Sex and the City’), and a pragmatic lawyer (who resembles Miranda of ‘Sex and the City’). The fifth friend, Zainab, brings the entrepreneurial focus to the group and often speaks up for feminist issues.

In Season 1 the viewers first get to know the girls in their new home, Accra, and follow them on their path towards making themselves at home there – finding houses, jobs and maybe eventually even partners. Once again similar to the setting of ‘Sex and the City’ the girlfriends have affairs that provide ground for the discussion of sexual and political topics, while the overall storyline focuses on Nana Yaa and her ‘one true love’, Shagun, the equivalent to Carrie’s ‘Mr. Big’. Even though the basic framework resembles that of ‘Sex and the City’, ‘An African City’ is more than just a franchise, as the writers manage to tailor the stories to the specific experiences of young Afropolitans and returnees, but at the same time address universal topics such as love and relationships that even non-African viewers can identify with.

2. Production and Resonance

Nicole Amarteifo, the producer and writer of ‚An African City’ could easily be a part of the group of girlfriends. She was born in Ghana, raised and educated in London and the US and went on to become a social media strategist for Africa at the World Bank before she returned to Ghana as writer and producer for ‘An African City’[4]. Using social media, she wanted to transform the ways of communication about Africa and encourage Africans to participate in that global discourse about their own future. However, she felt that especially the narrative about the African woman was not communicated adequately at all[5]. Inspired by the Nigerian writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie who speaks of the “danger of a single story” of Africa, Amarteifo wants to create a new story about the cosmopolitan single women of urban Africa, dismantling stereotypes dominated by war, poverty and famine[6]. Although she had a first idea for the show in 2009, Amarteifo started to work out the script properly in 2012, after she had moved back to Ghana. Despite the interest of various TV channels, she chose to produce the show independently, and to broadcast it via YouTube at first, where it is accessible for free to the viewers. In an article in The Guardian she is quoted: “By going online, I don’t have to be dictated by TV networks about what they do or don’t want to see. […] My show certainly pushes the boundaries – it is about five women who talk authentically about love and life, and that includes sensuality. People will be shocked, and some people will be angry – especially some African men. But by putting my show online I have the creative freedom to talk about these sexual politics. It is all about the conversation.”[7] The response was huge – both in Africa and abroad. Within a few weeks after its release, the collection of ten episodes had been watched over a million times, making it one of Ghana’s most successful YouTube channels. Not only African, but especially Western media picked up on the uniqueness of the show, its similarities with ‘Sex and the City’ and the cosmopolitan protagonists are an international sensation. Nicole Amarteifo’s expertise as social media strategist may have been a large contributing factor to the success of the show. The series’ homepage, its YouTube channel and the Facebook fanpage are regularly updated with exclusive looks behind the scenes, announcements, quizzes and newspaper features, keeping the fans involved with the show and even involving them in the production, as the commenting function is used to get immediate feedback. The show’s fast success and international reputation made it attractive to sponsors as well: Soon after the release of the 10th episode of season 1, the producers announced that there would be a second season featuring longer episodes and extended stories. The second season is now available online, but not for free anymore. Amarteifo and her producers chose to distribute it on their own website, charging 20$ for the entire season.

III. The Framing of Single African Women in ‘An African City’

Looking at various factors that influence the everyday life of single women, such as economic (in)dependence, social circumstances, sexual relationships and fashion or beauty ideals, this chapter aims to give an overview of how single women are framed in ‘An African City’ and to what extent the series succeeds at drawing up a nuanced and representative depiction of African women.

a. The Framing of Single African Women – Hard Factors

Part of the seminar ‘Single in the City’ was a closer look at the hard factors that structure single women’s lives such as governmental structures, political issues and economic independence, which is why we will have a closer look at the depiction of economic independence of single women in ‘An African City’.

Episode 2 of the first season of “An African City”, which is called “Sexual Real Estate”, starts with a short voice-over introduction about the economic situation of Ghana by Nana Yaa, who states: “In the country of Ghana, there are 25 million people. The housing deficit for the entire nation stands at about two million. And the cost of any nice home in the capital city, Accra: about the same cost of any nice home in Paris, London and New York!”. The opening scene that follows shows Nana Yaa with an estate agent in an empty apartment, where she is startled going over the rent requirements for the place: To secure the contract, she would have to pay 500,000 Dollars up front – cash even, pay 5,000 Dollars rent a month and deliver a security deposit of a whole year’s worth of rent, 60,000 Dollars, the very same day. When she points out that a constant electricity and water supply are not ensured and claims that her apartment in New York was cheaper, the estate manager dryly answers: “Well, this is not New York, unfortunately.” And he goes on to insist that people in Accra can actually afford this kind of apartment. In the following scene, the girls discuss the causes of the rising estate prices. Sade mentions rich Nigerian investors, Zainab adds the foreign expats[8], development agencies, and multinational firms to the list, which reminds her of another real estate issue: She is trying to buy a piece of land, but she suspects the agent is trying to sell the same piece of land to her and several other people. The girls’ conversation is symptomatic for the estate market in Ghana – it is portrayed to be overpriced and corrupted. Throughout the conversation Nana Yaa is proposed to move in with her parents permanently, as “it is completely acceptable for any unmarried woman of any age, here in Ghana, to be living with her parents”, as Makena points out. However, Nana Yaa’s spatial and economic independence in New York is an achievement she does not want to give up. Zainab suggests to look into a credit from Ghana Home Loans who offer mortgages for aspiring home owners. When Nana Yaa asks, if that is how Ngozi and Sade can afford their places, they both negate. Ngozi’s home is financed by her father, while Sade is supported financially by a “sugar daddy”, much to the disgust of Ngozi and the curiosity of the rest of the group. Sade claims “the answer to every woman’s problems [are] their so-called uncles”. Zainab heavily objects: “No, no, no. Not uncles. […] More like the root of all of society’s problems, the politics of the sexes. Listen! Men use their money and their power to get sex, you know this, and then women feel so powerless that they end up giving into the system. It’s craziness!” One might wonder, why the Ghanaian business men would be so willing to give women “anything they want” (Sade), and Zainab goes on to explain how investing in Nana Yaa’s apartment or lifestyle can be profitable for any “uncle”: “You act, like a man doesn’t have a plan! Take Nana Yaa, for instance: Everyone knows that her father is now the Minister of Energy. So, they may wine and dine her, but they know that after a traditional engagement and a baby – you will be having a baby, darling – they can count on some multi-million dollar oil deal! Nana Yaa becomes nothing more than an investment, a means to an end!”. Even though Nana Yaa is shocked by her explanation, she seems intrigued by the idea of pursuing a relationship with a rich man in exchange for material goods and financial support. The question whether sex has to be part of the deal is also discussed: While Makena claims she only has purely platonic relationships but still gets presents in exchange, Sade bluntly states “it’s not an exchange for sex, the sex is just a perk”. Nana Yaa agrees to be set up with one of her friend’s acquaintances, but Zainab also promises to get her in touch with Ghana Home Loans.

Over the course of the episode, Nana Yaa is dating Phillip Ofosu, a man twenty years her senior, who had become rich by trading oil. He deliberately pays for dinners and sends her expensive presents to her office on a daily basis (a dress by Christie Brown, a large Louis Vuitton bag and a silver bracelet), but Nana Yaa also starts paying attention to the world of politics and business, which according to her observations “was a world that was distinctly and exclusively run and owned by men”. And as his favours continue, Nana Yaa starts to worry if she is owing him anything in exchange. Again her girlfriends have different opinions, which they discuss over new hairdos and manicures at the beauty salon. On their way home, she and Sade talk about Sade’s reaction to running into the man who bought Sade’s new apartment at the salon with another woman, and it finally helps her make a decision. Sade is devastated at seeing the man she was sleeping with in exchange for a new apartment, telling herself that his paying for her apartment was only a nice side effect of their sexual affair, with another woman in public. “You’re hit in the face with the truth you’ve been avoiding all along. […] That you’re one of many, when you should be somebody’s one and only.” Nana Yaa decides to stop taking Phillip’s calls the next day and to takes up a credit with the bank which she calls her “own kind of sugar daddy”, who gives her financial and also sexual independence. She also decides to keep all of Phillip’s gifts as a reminder of what she will one day be able to afford by herself.

Nana Yaa is not the only one who is wondering over economic independence and the rules of courtship in the episode. Makena is shown to be going on a date with another repatriate, George, who had spent the last 15 years in Canada and now returned to work in the real estate business in Ghana. At first, they talk about how they met – at a funeral. From their conversation, it becomes clear that funerals in the Ghanaian upper class are not about mourning the deceased, but are regular networking events. Both confess to not knowing the deceased person, but attending the event trying to meet with different Ministers, pursuing their personal agendas. While George was successfully meeting the Minister of Housing, who offered him a large share in the national housing market, Makena’s chasing after the Minister of Foreign Affairs for a permanent job seems not to have been fruitful. At that point in the series it is only hinted, but her inability to score a well-paid permanent employment as lawyer is discussed often throughout the series. Even though she is a good lawyer, she has to work freelance and instead of being offered job positions, the interviewers use the opportunity to simultaneously decline her the position and ask her out on a date (see Season 1 Episode 3, “An African Dump”). Both Nana Yaa’s involvement with a rich business owner and Makena’s conversation draw up the picture of the Ghanaian world of politics and business to be tainted by nepotism, the repatriates – Afropolitans -, mostly following along the rules of the corrupted system without questioning them. As Nana Yaa concludes, it is still a world of wealthy men in which women, no matter how educated, do not seem to have a place (yet). The difficulties for women who aim to be financially independent are not only addressed on the level of state politics and business enmeshments, but also on the level of personal relations. When their date comes to an end and the bill is delivered to their table, Makena takes offense at George asking her to pay for half of their meal. Later, at the beauty salon, the girls talk about their declining willingness to “go Dutch” (pay half the meal) and whether it is old-fashioned or anti-feminist. They state that as well-educated, formerly living abroad and not poor women, they should know better than to take offense at their being considered equal partners when it comes to finances. However, the fact that most interpersonal interaction is characterized by male dominance and paternalism, the girls have become used to an inferior position, and even embraced the advantages of ‘being wined and dined’ and the promise of a free meal even if the date partner is not convincing.

The Episode “A Sexual Real Estate” is a showcase for the political undertone of the series. It brings to light very structural issues that characterise the lives of modern (single) women in Ghana. Nana Yaa gives the different ways of financing a comfortable life a try, but does not want to lose her independence that she has become used to while living in New York. Makena is offended by her dating partner’s request at first, but later critically reflects on her reaction with her girlfriends. The protagonists find possible solutions that can serve as examples for the viewers who most probably are familiar to those kinds of situations. All throughout the episode, arguments in favour and against certain opinions are mixed with humorous interactions, the script cleverly weaves statistical facts, political discourse and feminist positions together, framing the protagonists as strong-minded and independent but relatable women with differing opinions who can serve as role models for the viewers without imposing a definite solution upon them. If one pays close attention, there are many more political references to be found in the episodes: Episode 6 (“He Facebooked Me”) touches on the Africa Growth and Opportunity Act while Episode 9 (“#TEAMSADE #TEAMNGOZI”) brings up training female cooperatives, HIV awareness and entrepreneurial issues with tax authorities.

The second season of ‘An African City’ continues to address serious problems that single African women are facing but that are only rarely discussed in popular media: Problematic mother-daughter-relations and even sexual harassment and rape.

Illustration 2: Screenshot of the series’ Facebook fanpage, where current episodes are promoted and fans get the chance to immediatley reply and giving space to public discussions.

(source:https://www.facebook.com/anafricancity/photos/a.486373964801861.1073741829.265654806873779/805096392929615/?type=3&theater)

b. The Framing of Single African Women – Soft Factors

1. Relationships

The relationships the five main characters are in, their ups and downs, and of course love are a recurring topic in almost every episode. Behavioural failures from their male counterparts are reasons for ongoing discussions and show their dissatisfaction with them. Never the less in the end it always seems that most of the girls are looking for someone special or in particular that ‘one big love’. The show mainly focuses on Nana Yaa´s search for her ‘romantical aim’ but the idea of one big, romantic love seems somewhat familiar.

Season 1 Episode 3 (“An African Dump”) starts with the five of them located in Nana Yaa´s brand new apartment. Each of them contributes an apparently inadequate behaviour of their current partners. Zainab starts telling how she is constantly disturbed in her sleep by her boyfriend´s snoring. Makena tries to excel the story with her own current lover who has a particularly strong mode of transpiration in the most improper situations. This story is only outplayed by Nana Yaa´s partner Kofi, who has the habit of announcing that he has to use the bathroom in a very frank way, and that on a daily morning basis. For all of the women these are severe reasons to overthink their connections to their partners but also a source of amusement. Later in the episode Nana Yaa really breaks up with Kofi over this issue. It is only in the end of the episode that we learn the real reason she ended her short romance with him. She has an encounter with her ex with whom she is still in love and openly admits that Kofi´s ‘verbal bathroom habits’ were just an excuse to end a relationship that she never really wanted.

This example describes quite clearly how single women in ‘An African City’ are being framed in terms of relationships, men and romantic concepts. Men seem to be replaceable at any time and can be both, a source of frustration and amusement. Whereas the audience experiences only very few details during the series about the current, male counterparts of the Zainab, Makena, Ngozi and Sade, Nana Yaa´s history and love for her ex-boyfriend Shagun are narrated in a recurring story. This example particularly shows how critically male habits are discussed in a group, which at the first glance creates an atmosphere of sheer superficiality. The women seem to rationally analyse and observe every detail of their partners in order to efficiently find a perfect counterpart. Such thinking of efficiency, rationality and optimization are commonly accepted to be typically male character traits, so the five women whose femininity is explicitly visualized in their outer experience, show a somewhat male behaviour in terms of relationships. This very same behaviour is later revoked when Nana Yaa encounters her ex and suddenly realizes that she was not rationally considering the misbehaviour of her former partner but was secretly still in love with her old partner. The twist in the story line displays now, contrary to the before emphasised masculinity, a very emotional connotation of women in general, as her friend suggests that she might have suppressed her feelings, and the leading character in particular. It all comes back to a very stereotypical role model that has been practiced over several media, such as television, books and in general through a long period of time. Moreover, it reveals a lot of parallels to the famous series ‘Sex and the City’ which has been the model for ‘An African City’. In both series that take place on different continents the producers felt obliged to create a romantically and emotional picture of the women that are on display. Both revealing that this is an ideal many women can identify with.

2. The Returnee Issue

Another particularity that frames the five women in the series is their common background in having lived and studied abroad. As they have now returned home they encounter a variety of difficulties and changes which they need to adapt to. The returnee issue is one of the features that repeatedly comes up over the first ten episodes of season one and has its own terminology. Taiye Selasi has defined the word Afropolitans’ in her essay ‘Bye-Bye Barbar’ which describes the five main characters in ‘An African City’[9]. The word ‘Afropolitan’ refers to a person, male or female that belongs to an elite, African born segment, having been raised and educated outside of Africa in the United States or Europe. Selasi comments that “We are Afropolitans – not citizens, but Africans, of the world”. Her essay describes this movement quite well but also the insecurities the returnees face when they come back to their home country. Typically, they encounter issues with ‘double identities’[10]. They are faced with a culture that is supposedly their own but has been replaced to a large extent by the habits and cultural norms they have experienced outside of Africa, where they have spent most of their lives. This issue is also addressed in ‘An African City’.

The ‘double identity’ is addressed in various ways and becomes almost a necessity of the character of each woman. Misbehaviours, like handing over the menu to the waiter with someone’s left hand (Season 1, Episode 1 “The Return”) or water rationing and power shortages are just a few of the new standards and etiquettes the characters have to adapt to. One specific moment that painfully describes the loss of the main character’s mother tongue is an encounter between Nana Yaa and her ex-boyfriend Shagun. Shagun introduces his new girlfriend who speaks to Nana Yaa in their Ghanaian mother tongue. Unfortunately, she is not really able to respond, as she has not been living in the country for quite a while. The situation culminates in an awkward moment when the main character of the show is visibly embarrassed and feels inferior to her successor. Over the following episodes she strives to practice her mother tongue again and admits in Episode 5 (“The Belly Button Test”) that she felt ‘less of a Ghanaian’ when not being able to speak a local langua. Struggles with their regained cultural environment are quite frequent and become a particular aspect of the five women. Their quite successful achievements and cosmopolitan education outside of Africa, are opposed to their partially weak seeming skills to adapt back home. Cultural reintegration becomes an important issue in the series and defines the identities of the five single women portrayed in it. The struggle with identity adds on top of their search of partners and describes their situation as more difficult than it might have been outside of Africa. Even though this might not be applicable to all women living in Accra it definitely has a large potential for identification with general social struggles.

3. Fashion

Another aspect single women are framed with in the series that has certainly a strong visual effect are fashion and beauty. Fashion can tell the observer a lot about the people and can moreover serve as ‘[…] an analytical tool for examining various aspects of cultural significance.’ [11]. The clothes and designers which are shown on ‘An African City’ are chosen consciously in order to convey certain messages to the audience. Afua Rida, who is the stylist of the show[12] has created a certain look for the five main characters which tells a very specific story. Moreover, the show supports various African fashion designers by showing their creations. African fashion has only more recently gained attention from the international market but designer who come from the continent have already been spread all over the fashion industry before[13]. One famous example is certainly Yves Saint Laurent who was born in Algeria and the first one to introduce African clothing, patterns and models to the public in the 1960ies and 1970ies[14]. The clothes shown in ‘An African City’ are from the collections of local Ghanaian or even Accra based designers. This is not just for the purpose of being more authentic in terms of clothing but also to promote the talent of unknown designers. Moreover, the clothes are sending a visual message to the audience of the show and frame the five characters in a specific way.

Illustration 3: Promotional Picture for Season 1 of ‘An African City’

(source https://www.jwtintelligence.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/An-African-City.jpg)

If we look at the promotional picture for Season 1 (Ill. 3) of the five women, we can find many clues as to how single women in Accra are being framed in terms of fashion. Zainab is placed at the far left side of the group wearing a beige, pinkish floor-length gown that has a thigh-high slit and plunging neckline. The material is soft and figure-hugging. On her shoulders and to the left and right side of her waistline there are patches of a different sort of black and white graphic cloth. The pattern reminds strongly of traditional African cloths. To her right is Ngozi who also wears an ankle-length, strapless gown with a sweetheart neckline. It has a deep mustard-yellow colour and a graphic, purple, round pattern on the skirt. While the upper part of the dress is tight and made out of ruffled, plain material, the skirt is parted in the middle and creates the idea of a short and a long skirt above each other. The pattern reminds again of traditional African clothing but the cut of the dress seems to be strongly Western. Nana Yaa is placed in the middle of the group, wearing another floor-length dress. It has a one shoulder strap with large ruffles on the other top half is made with a sweetheart neckline. The dress is formfitting with a mermaid shaped skirt and an emphasis on the waistline with a belt. A bright pink floral pattern almost entirely covers the white background of the cloth the dress is made of. The colourful, bright pattern once more reminds of traditional African cloth and the shape of the dress is made in the style of a Ghanaian Kaba. Makena is standing to her right side, again wearing a floor length, tight, see-through greyish dress. It has long sleeves and a high neckline. The material seems to have a very, rich floral, silver and grey pattern that equally covers the entire surface. Once more the shape of the dress is not particularly African but the rich pattern might indicate such a reference. Sade is on the far right side of the image wearing a cut-out, calf length dress. The skirt has a beige colour whereas the upper part is made with a light yellow and a black and white leopard print material. The neckline is embellished with a wide, white pearl necklace that has several layers. What carries an African reminiscence again is the leopard print material that is used in the top part of the dress.

All of the dresses, which are representatively shown in this image, support the message that is conveyed during the series and aligns with the idea of ‘Afropolitans’. The five prevalently single women whose stories are told in ‘An African City’ are the embodiment of a new generation of Africans that has been raised and educated around the globe and is increasingly returning to their home country. The clothes not just in this example but throughout the series always show a combination of traditional African wax prints, opulent patterns and accessories in combination with Western high-fashion inspired shapes. They symbolize the social affiliation of the five main characters with this group as they are themselves a combination of traditional African and Western influences. African fashion designers have already been described as “grounded in traditions but exposed to international tastes, thereby allowing them to both satisfy local demand and ignite interest abroad.”[15]. This is also the essence that is shown in the clothing which is used in ‘An African City’. Moreover, it is equally true that the series has also sparked interest outside of Africa. The clothes just like the five portrayed characters are relatable concepts for women all over the world, thus emphasizing the similarities across cultures.

4. Beauty Ideals

Another recurring topic are the prevalent beauty ideals that exist in Africa and pose quite a challenge to the leading ladies of the series. Throughout the show some of the characters follow the trends but others are trying to resist and stick to their own ideas of what looks good and what does not. Single women in Accra seem to be worried about their appearance and current beauty trends, which does not seem any different from women elsewhere on the globe.

One of the first mentioned beauty or body-ideals is the weight someone has. In Season 1 Episode 1 (“The Return”) Sade meets her aunt while having dinner with the other girls. Before saying goodbye to her, her aunt tells Sade how ‘fat’ she looks. Except for Nana Yaa all of her friends have a knowing look on their faces and nod. They compare the times some has called them fat, since their return as this is seen as a compliment in Ghana. Compared with many Western countries this is a quite different body ideal, as most of the Western world cultivates a very strict diet and strong physical exercise in order to be as healthy, skinny and in shape as possible. Moreover, being fat or overweight is something that is regarded as an illness and highly criticized not only scientifically but also socially. Coming from this part of the world and being confronted with a completely different body-ideal the single women in the series seem to struggle with their self-confidence. Never the less they approach the issue with amusement as the have been counting the times they have received such compliments and compare them competitively with each other.

In Season 1 Episode 5 (“The Belly Button Test”) Zainab is confronted with another beauty ideal. As she is about to pay the items she bought at the drugstore the lady at the cash register offers her a small tin with bleaching cream for her skin, commenting “You would be so beautiful if your weren´t so black.” (See Season 1, Episode 5 “The Belly Button Test”). She further elaborates that she has been using the very same product and will soon have a skin tone comparable to famous artist and songstress Beyoncé. The process of skin bleaching in order to receive a look that is perceived as more beautiful, is widespread across the continent of Africa. It is seen as a status symbol and is becoming increasingly popular with young, well-educated cosmopolitan women, as opposed to its earlier prevalence with poorly educated women in rural areas[16]. What seems to be underestimated are the dangerous side effects of the product´s toxic ingredients which can cause severe damage to skin and body[17]. Zainab´s reaction in the shop shows her disagreement and lack of comprehension for this procedure. She is confronted with a beauty trend and ideal that is not only dangerous but moreover pursues an ideology in favour of “[…] the desire for and consumption of Western culture and products.”[18]. This adds another part to the frame the characters in ‘An African City’ are put in. Skin-bleaching is a highly controversial beauty ideal not just in terms of health but also ethically. It promotes the idea that being a natural African woman is not good enough for society. Moreover, it supports an outdated colonialist idea of ‘white supremacy’[19]. In the show their approach to the topic is certainly one of disapproval but at the same time shows the pressure which exists within society to have a light skin-tone.

In the very same episode Nana Yaa has a quite similar encounter with another beauty ideal that is prevalent amongst African women. She is desperately looking for a hairdresser who does ‘natural hair’. In the shop she enters, she has a short conversation with a woman who works there and asks if they wash and blow-dry but she refuses. In addition to that the shop worker replies that they only do perms and even asks her why she does not do one. Nana Yaa just like Zainab before in the drugstore shakes her head in a lack of comprehension of this beauty ideal. Later on when meeting with the girls in a restaurant she discusses her amazement that even in Africa she cannot find a hairdresser who follows a natural hair ideology. Sade and Makena agree with her but admit to having succumbed to the ‘hair pressure’ since they came back. Makena has a perm and Sade is wearing different wigs throughout the entire season. There is a long history of juxtaposing Black hair with Caucasian hair in order to show that Black hair is in need of treatment to approach a Caucasian look[20]. Even though these tendencies seem to be somewhat changing it is apparently a very dominant phenomenon on the African continent. The women in the series discuss the hair style critically but in the end still go along with it, except for the main character who somewhat bravely resists the common social pressure that is also exerted on her by her own mother. Even if they have moved back to their home country they are confronted with a strongly westernized beauty ideal, but the series frames both sides of the movement. Nana Yaa stands symbolically for the young generation of ‘Afropolitans’ who refuse to adapt to mainstream ideas.

IV. Conclusion

An African City contributes a major part to the delineation of single African women. It displays a generation of young “Afropolitan” female singles that encounter daily struggles. In conclusion one can say that they are portrayed not much differently from any woman that is shown in Western series or other media. The series casts light on common issues many women, single or not can relate to but also on topics that are particularly connected to Africa.

One of these general frameworks for single Afropolitan women is their partial efficiency in their search for partners which is countered by another hopelessly romantic gaze on their concept of love in general. In this respect the Series follows classical stereotypes of emotionally uncontrolled women. Another more specific topic that is treated in the series is the returnee issue Afropolitan women face upon returning home. The troubles they face adapting in their native country or continent after such long time abroad, become part of their distinct depiction also complicating their romantic search for love. In addition to that fashion becomes an important medium to visually transport the “double identity” the five main characters are portrayed with. The colourful and stylish outfits shown in “An African City” visualize a combination of traditional African clothing elements with Western high-fashion ideas and therefore also the identity of the five girls themselves. This also emphasizes women´s interest in fashion and their pursuit of certain beauty ideals. The ideal beauty also comes into focus and of course the struggle to align with certain trends. Even though the trends, such as a light-skin tone, a certain corpulence and wearing wigs may be somewhat different from other parts of the world, they address a common female struggle.

It has been vividly discussed in the media, especially social media and blogs, whether the show truly represents “the urban African woman”[21]. As Akinyi Ochieng concludes in her article “Is ‘An African City’ A True Portrayal Of The Urban African Woman?”, the protagonists of the show stand for different concepts of modern-day womanhood in Africa that might seem contradictive, but essentially are all valued as equally valid life choices for African women, making the show appealing for all kinds of viewers. Written and produced by all women, telling a story that involves men as supporting characters only, ‘An African City’ offers a female gaze upon sex and relationships, and life in a large African city in general. Naturally, the focus on five women from the upper middle class may seem limiting at first, but after all, ‘An African City’ frames African women in a way that shows cultural particularities but in general provides a picture that is not much different from any other women in other capital cities around the globe. Therefore, the series for once does not only provide a different image of African women in general, as the producer of the series intended but also some sense of universality and relatability to women all over the world. Nicole Amarteifio has achieved her goal: We get to see a whole different kind of modern African women on television, one that exists in reality, and one that we might not have known before.