A visual essay by Chengchen Tian

Theoretical Framework: A Hybrid Influence of the Tradition and Modernity

Chinese have long been emphasizing the concept of family, since families are core elements that constitute the nation state and the family unit is the main source of citizens and labor force. According to the Confucian tradition, people who want to achieve a successful career must primarily be expert in family business. People’s role and identity is firmly related to the kinship position and a stable family can contribute to the peaceful society. (Gaetano, 2009:02) On the other hand, it is the marriage that leads to the formation of the family. It is no wonder that the progressive spread of singlehood and shift of family patterns in China attract great attention. Virtually, a lot of academic researches attribute the phenomenon of increasing singlehood to the modern development of Chinese society, which means the social changes such as industrialization, urbanization, equal access to education and labor force do empower women and provide them with various of choices. “Modern” and “traditional” are always regarded as dichotomous categories, as “modern” is frequently labeled as independence, autonomy, choice, freedom, individualism and equality, while “traditional” reminds people of patriarchy, repression,authority, inequality. (Harkness and Khaled, 2014) Thornton (2013) claims that “modern” and “traditional” are too much delineated as two opposite ends of a linear development model. Parental pressure, forced hypergamy and male dominance are treated as tradition while love marriage, women’s independence, free choice and gender equality are seemingly undoubted modernity when it comes to family and marriage. Many papers illustrate the contrast between tradition and modernity. For instance, Situmorang(2007) believes the educational attainment and labor force participation, which provide women with independence and more choices, help to explain the delayed marriage and increasing singlehood. Moreover, there is positive association between education and employment. Women have to take different kinds of measures, for example, take the annoying comments jokingly or pretend to be married, to avoid the pressure from social stigma. Gaetano also holds that the new expectations and desires for career become an alternative to the marriage, conflicting with the rigid gender norms. (Gaetano, 2009:17) It is likely that all the ‘rotten traditions’ will end with modernity. However, it is a Eurocentric idea that all the traditional systems will transition to the modern patterns, especially in the non-western context. Lahad maintains that choice can be a discursive force that enables women to resist traditional norms, but the centrality of choice in the construction of intimate relations simultaneously delegitimizes women’s individuality and autonomy. She critics the post-feminism, choice-feminism and neo-feminism promotes a false sense of autonomy by excessively accentuating the value of autonomous choice without considering the sociocultural context that construe these choices. (Lahad, 2013: 03) Zurndorfer(2015) finds that materialism and consumerism appear hand in hand with the rapid economic growth and urbanization in China, resulting in the development of China’s sexual economy. Stacey(1982) associates the complicated and paradoxical Chinese family system with Chinese Communist Party’s policies and analyzes the historical factors that lead to the policies, concluding that the CCP actually advocates the “New Democratic Patriarchy” in China. On the one hand, the CCP explicitly undertakes the family reform, supporting the destruction of Confucian patriarchy and the creation of what CCP calls the “new democratic family”, which promotes free choice, monogamous and heterosexual marriage with equal rights of the sexes. On the other hand, the CCP contradictorily adopt the implicit family policy to consolidate the deeply ingrained Confucian tradition and patriarchal family system to win the support from rural space. The dual level policy can partly account for the coexistence of traditional and modern family patterns in China. Ji(2015) also notices the resurgence of patriarchy in China. By investigating how China’s so-called “left-over” women negotiate their marriage and careers, she finds that traditional gender norms still regulate gender relations and family life in the private sphere, and the tradition and modernity coexist in a transitioning China. In a summery, in a society where most people are deeply influenced by the traditional culture, the modern development brings new energy to the society while simultaneously add new challenges to the interaction between tradition and modernity. Moreover, the shift of family patterns and the progress of women’s status is a hybrid consequence of the tradition of modernity instead of the modernization.

Marriage, A Weighty Topic to Talk About?

China has attracted great attention by high-speed economic growth in the last decades. Benefiting from the economic miracle and modern development, Chinese find it easier to make money to meet their basic needs, which is a dream pursued by their elder generation. However, what is to their surprise is that most young people are sensitive to talking about marriage, since they can’t afford the high cost of the marriage today. Following the Confucian tradition that men act as the breadwinner and women deal with housework, the bridegroom should transfer the betrothal gifts to the brides’ family to thanks for raising the girl. Although nowadays women gain access to education and enter labor market, the custom continues in most Chinese families. And the booming economy also witnesses the change of betrothal gifts from “three old things” to “three new things”. The three things shift from “watch, bicycle and sewing machine” in the 1970s to “house, car and money”(Picture 1) in the 21 century. Millions of young people flood into the cities to participate in the urbanization and modernization, thus possessing a house in the city becomes a prerequisite of marriage. In the last ten years, the urban real estate price has tripled,even people from the middle class family find it difficult to afford the real estate. As a result, it becomes a huge economic burden for men to enter a marriage, especially in a context where exist dramatic imbalance of sex ratio due to the Confucian patriarchy. And the rapid development of Chinese real estate economy is always humorously translated into “mother-in-law economy”(zhangmuniang jingji), since it is always the bride’s mother that makes the house a must, which promotes the consumption on house and economic growth. But the elder generation also claims that it is for the sake of their daughter’s happiness, how can their daughter live with a “homeless” man? John Osburg (2013) finds that single women in Chengdu (Sichuan Province) prefer to find a partner with “good economic condition” (you tiaojian), men without these “essentials” will suffer from a feeling of “emasculation”. Zurnforfer (2015) claims that the urban real estate inflation catalyzes the sexual economy, making materialist women exchange femininity and sexuality with monetary asset with property. In general, the burden of marriage is a hybrid result of the traditional norms and new problems in modern development. The traditional gender norms still work in family life as men should play the role of supporting the family, and the mammonism, materialism and consumerism put extra pressure on people to enter a marriage.

Fig. 1: Cash as betrothal gift. From: image.baidu.com

Education, Career and Marriage

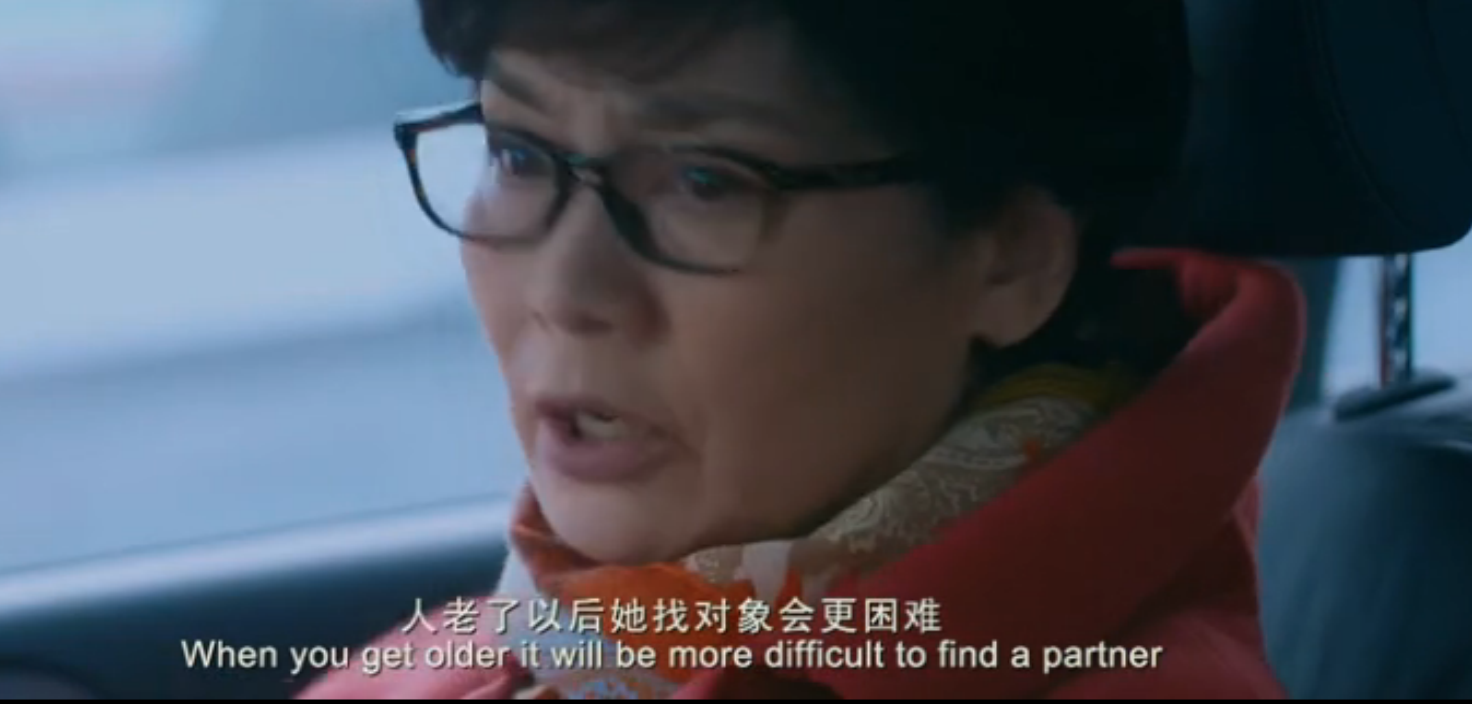

“Modern” is always firmly associated with independence, choice, freedom, and women’ access to education attainment and labor force participation is treated as ideal ways to emancipate women from the traditions and reduce their dependence on man, which is significant in achieving their “modern” goals. However, the binary distinction between tradition and modernity is often blurred in transitional society. Does women’ achievement in career empower them to enjoy more freedom? To what extent does the education enhance their choices with regard to marriage? Can the economic independence bring about real independence in choosing their marriage? The Chinese movie “the last woman standing”(剩者为王,if we translate it word by word, the name is “the leftover women is the king”) can help to answer such questions. [1] The movie is adapted from the novel with the same name by a female writer, LuoLuo, who is also the director of the movie, focus on the life of a single women, Sheng Ruxi. Sheng is a white collar with great success in her career, but she still keeps single even she passes her thirty-year old, an sensitive age since women are traditionally treated as “leftover” after thirty in China. She sticks to her principle that she only marries someone with romantic love, regardless of the opposition from her well-educated family. (Picture2) Unconsciously, she falls in love with her new colleague Ma Sai. But Sheng’ s mother spares no effort to stop them getting together and ask Sheng to get married with a doctor who is elder and with high salary. Sheng’s mother achieves her goal of separating the couple by pretending to suffer from disease and invoking Sheng’s loyalty to parents and family. Finally, Sheng’ father tells the doctor the girl’s persistence on romantic love and helps Sheng and Ma get reunited. The movie helps to illustrate that the private sphere of the family is still regulated by traditional gender norms despite the achievement for the women in some public spheres, such as the education and career (England, 2010). Actually the economic independence of women doesn’t necessary bring about women’s independent choice on marriage. Nevertheless, contrary to England’s idea that men tend to remain relatively traditional although women have become more progressive in their gender ideology, it is plausible that pressure on the young women mainly come from their female family members and friends. Situmorang’s study of unmarried women in Indonesia (2007) also demonstrates that women shoulder the pressure to get married from their female relatives. Moreover, the elder generations show more traditional views towards marriage even they are well educated. In other words, the young generations are more open to accept the “modern” concepts. However, the most significant issue here is that although many women are looking forward to romantic love, they have to mediate between arranged marriage and love marriage. There are many factors eventually determine their choices on marriage, for instance, their loyalty to family and filial piety, friends’ suggestions and their own persistence on marriage. Individuals are influenced by modern ideations blended with traditional cultural norms and they make choices as a hybrid consequence of tradition and modernity.

Fig. 2: Sheng’s mother’s attitude towards marriage. From: “the last women standing” (movie).

Women’s Rising Decision-making Power in Collectivized family

Last part exhibits that individuals’ interest to some extent should be subordinated to the needs of family, why do Chinese family focus on the common interest of the whole family members instead of individuals’ happiness? Is it possible that women show more visibility in making contribution to the family decisions due to the help of Confucian tradition apart from their participation in education and career?

As a matter a fact, male dominance has been a concentration in family studies. The patriarchal perspective emphasizes the hegemonic influence of patriarchal norms, which reinforces the predominant role of man in both private and public spheres. (Blumberg, 1991, Ferree, 1990) Resource theory claims that husband and wife bring different values of exchange resources to the relationship. (Xu, 2002) Both theories attribute women’s invisibility to their traditional domestic responsibility. However, both theories can’t precisely explain why Chinese couples in cities jointly make family decisions and the wife is more frequently the decision maker in the family (Feng, 1995), which can neither be easily explained by the rise of feminism.

It is beyond doubt that women’ participation in labor force attenuate women’s dependence on men in China, thus promoting the shift from men as the breadwinner to mutual financial dependence of working husbands and wives in the family. However, it is necessary to take the Chinese collectivized family mode, which is characterized by the placement of family interests over personal needs and fulfillment of each member’s obligation to the family to achieve relational harmony, into consideration. (Zuo and Bian,2001) Different from the individualized family in the industrial West, which recognizes the pursuit of personal interest and associates family power with the mode of direct equity-driven exchange(imbalance of resources brought to the marriage, Brines and Hoyner,1999), the Chinese collectivized family, shaped by the household agrarian economy and Confucian ethics, accentuates the collective interest and supports the indirect marital exchange: family members fulfill their responsibility to the family under the norms of relational harmony and mutual trust. (Treas, 1993) The core value in Chinese family is “sacrifice, contribution, responsibility”. In other words, family members can try to maximize the profit of the whole family at the expense of one’s own profit. Therefore, women’s household ability is fully received as a contribution to the family interest since men and women cooperate to improve the living conditions of the family.

Due to the influence of collectivism, it is not a surprise that a lot of couples jointly make family decisions in China. However, the women are more frequently to initiate the suggestions and make the final decisions because the household responsibility generates power. (Ji, 2015) The traditional breadwinner-homemaker mode has transformed into “men deal with how to make money, women deal with how to spend money” mode. It is always the women play the fundamental role to deal with daily business to sustain the healthy function of the family,especially in controlling and allocating financial property of the family. On the one hand, the doers has superior knowledge and experience in making family decisions, they can make a better choice which will finally benefit the family. On the other hand, women’ time and energy spent on housework responsibility can be translated into their love to the family, their contribution to the family should be recognized as the right to make decisions (Hood,1983). Nowadays it is common to see Chinese women to manage family affairs and determines both daily routines and major affairs such as insurance, children’ education, investment of family assets. Simultaneously, women also complain that “even though he knows the children’s teacher’s name or knows where to buy the daily food in the supermarket, I would let him to dangjia (rule the family)”. (Picture3)

Fig. 3: Women shopping in the supermarket. From: image.baidu.com

Conclusion

China has embraced urbanization and mass education after economic reform since 1980th, providing women with mobility and independence as they have more access to education and labor force participation. Alongside the modernity, the Confucian patriarchy continues to influence Chinese society since women are still treated as mothers and wives despite their achievement in career. In a transitional society where tradition and modernity coexist it is worth considering the strength and weakness of both instead of treating tradition-modernity as a linear development. It is beyond doubt Confucian patriarchy put great pressure on single people in China, but it is also the fact that women are increasingly to be the decision-maker in the family since their household responsibility is well recognized and firmly associated with power in the collectivized family. On the other hand, the modern development brings women opportunities to equally attain education and makes career as an alternative, while women simultaneously have to be confronted with new problems such as consumerism and materialism, let alone the fact that the so-called free choice doesn’t always provide them freedom since traditional gender norms still regulate gender relations and family life in the private sphere. As people in urban China are influenced by modern ideations blended with cultural norms, it is plausible that they will negotiate between tradition and modernity and make dynamic choices in different situations.

References

- Augustina, Situmorang (2007). Staying Single In a Married World, Asian Population Studies, 3:3, 287-304.

- Blumberg, R. L. 1991 “Income under Female versus Male Control: Hypotheses from A Theory of Gender Stratification and Data from the Third World,” Pp. 97-127 in R.L. Blumberg (ed.), Gender, Family, and Economy. Sage Publications.

- Brines, J. & Joyner, K. 1999 “Principles of Cohesion in Cohabitation and Marriage.” American Sociological Review 64: 333-55.

- England, P. (2010). The gender revolution uneven and stalled. Gender & Society, 24, 149–166.

- Feng, L., Anderson, В., Wang, S., and Zhang, J. 1 995 Research on Marriage, Family and Women’s Status in Beijing. Beijing: Bejing Economic Institute.

- Ferree, M. M. 1990 “Beyond separate spheres: Feminism and family research.” Journal of Marriage and the Family 52: 866-884.

- Gaetano, Arianne. (2009). “Single Women In Urban China and The ‘Unmarried Crisis’: Gender Resilience and Gender Transformation” Working Paper No31: 01-18.

- Harkness, G., & Khaled, R. (2014). Modern traditionalism: Consanguineous marriage in Qatar. Journal of Marriage and Family, 76:587–603.

- Harriet, Zurndorfer (2015). Men, Women, Money, and Morality: The Development of China’s Sexual Economy, Feminist Economics: 01-25.

- Hood, J.C (1983). Becoming a Two-Job Family. New York: Praeger.

- Ji YingChun(2015). Between Tradition and Modernity: “Leftover Women in Shanghai”, Journal of Marriage and Family: 1057-1073

- Judith, Stacey(1982). People’s War and The New Democratic Patriarchy In China. Journal of Comparative Family Studies. Vol.13, No.3. pp. 255-276

- Kinneret, Lahad (2013). The Single Woman’s Choice As a Zero-sum Game, Cultural Studies, 01-28

- Osburg, John. (2013). Anxious Wealth: Money and Morality Among China’s New Rich. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Thornton, A. (2013). Reading History Sideways: The Fallacy and Enduring Impact of the Developmental Paradigm on Family Life. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Treas, J.(1993) “Money in the bank: Transaction costs and the economic organization of marriage.” American Sociological Review 58: 723-734.

- Xu, X. and Lai, S. (2002). “Recourses, gender ideologies, and marital power: The case of Taiwan.” Journal of Family Issues 23: 209-245.

- Zuo, J. and Bian, Y. 2001 “Gendered resources, division of housework, and perceived fairness: A case in urban China.” Journal of Marriage and Family 63: 1 122-1 133.

[1] The market- driven media, such as TV series, movies and magazines, is regarded as effective way to reflect public views since China has strong control on mainstream media.