A Visual Essay by Nina Petrovic

Introduction

There is a wide range of fear landscape: fear of dark, fear of abandonment, fear of losing someone or something, fear of the unknown, fear of failure, fear of disease, fear of getting emotionally or physically hurt, fear of natural or unnatural powers, etc. However there is one fear that encompasses all previously mentioned and that is fear of losing one’s life. Namely, the fear of death is the common characteristic of all humans and all living beings in general, which actually serves as impeller for survival and for prolongation of the life of all species. In order to escape from the danger that was threatening from the nature and to make a life easier to survive humans built settlements, and with that creation of the safer places (in comparison with the natural surrounding) the creation of the new dangers was born. Namely, especially the formation of large settlements such are cities became a new jungle where danger is lurking from every corner.

“Violence against women and girls does not emerge from nowhere. It is simply the most extreme example of the political, financial, social and economic oppression of women and girls worldwide”: United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki–moon at an Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) event at Headquarters in 2014.

Apart from the everyday violence in the city that women face in greater extent in comparison with men, regardless of their age, class, ethnicity, nation or country, women are from the very beginning and especially in patriarchal societies constructed as threatened group. Furthermore, men are viewed and positioned as fearless and fear-provoking and women as fearful and passive and victims. Although, fear of violence is present in private spaces that are shared with family members or acquaintances, in this paper I will focus on the fear that is generated in the public spaces which are shared with strangers and I will tackle the issue of visibility of women in public space and their right to reclaim that space. Furthermore, I will try to show how it is possible to address and conquer fear in Indian big cities in a unique way, using the example of a Fearless Collective, a young artistic movement in India, as a case study. In order to answer my research question, What landscapes of fear is the Fearless Collective responding to?, I will focus on the work of one artist, Shilo Shiv Suleman, the founder of the Collective and try to look into the strategies of the Collective that lie behind her street art projects and to describe some of her wall painting projects that are noticeable and I will try to examine the role of art in social activism within this particular case.

Fearless Collective

Fearless is a collective of artists, feminist activists, photographers and filmmakers across India that deploys art to speak out against gender violence. It was formed in response to the gang rape that took place in Delhi in 2012, to attempt to (re)define fear, femininity and what it means to be fearless, particularly because protests generated a lot of fear which was absolutely counter-productive to the change India needed to see. What they needed are more women out on the streets, reclaiming their right to public spaces and equality. More to add, it owes its name to the victim who was honoured as a brave woman and popularly named Nirbhaya (The Fearless). Fearless is based in India and it was founded by the contemporary artist and a visual storyteller, Shilo Shiv Suleman, and is managed by her and a core group of volunteers. Two main characteristics of this collective is that it creates public art as a dialogue about gender, sexuality and equality, and that it reclaims one’s right to public space. Unlike, globalized image of feminism, Fearless is exploring new horizons, using mythological and cultural figures and re telling those stories with a new and radical point of view. Today, over 400 artists across India, Pakistan and Nepal form part of Fearless Collective and are involved in participative storytelling in public space.

Right to Public Space

Streets of Indian cities are public spaces that value woman’s body as a liberalized commodity. Women feel that they are constantly observed and judged because of their cloths, behavior, where they are heading to and what is the purpose of that, who they are with, at what time of day or night. More to add, they are under pressure to conform to the boundaries that their tradition and class set. Often private and public space are seen as to contradictory sides, and that private space is a space of women and for women and that the public space is a space of men and for men. However, in patriarchal societies, we do not even have to take a closer look into those domains, because of the obvious fact that is embodied in the every aspect of patriarchy and that is the male dominance. Men have the primary power, moral authority and social privilege.

“Public and private space should not be understood as mere opposites, each with its own independent set of characteristics. And that is only if we understand the public and the private as complementary- rather than oppositional-spheres that we will be able to understand the ways in which masculine and patriarchal power operates in society.” (Srivastava, 2012)

That is the reason why it is often said that revolution for India’s urban women must start at home.

Women are facing violence or threat of violence everywhere, at home, in the street, public transport, at school or at work, during the night and day, regardless of their caste, ethnicity, age or what they wear. The fear of violence not only locks women in the cycle of poverty, making even wider gap in the economic inequality if she agrees to stop working, but it can also lock her in much greater psycho-social cycle from which she cannot escape and which makes her easy target to be manipulated. Therefore The Fearless Collective is calling on women to stand together and take part in producing their own space and to enjoy it, even if at times it might look that art is useless in such situation.

“It is imperative to engage with the question of women’s rights to public space as citizens, posing a counter voice to not just the voices of moral policing but also to challenge the centrality of the discourse of safety even among those protesting government inaction. I have argued earlier that what women need in order to access public space is not conditional safety but the right to take risks“(Phadke, 2005).

“The question of making streets safer for women is not an easy one, because the discourse of safety is not an inclusive one and tends to divide people into “us” and “them” tacitly sanctioning violence against “them” in order to protect “us” “(Phadke et al 2009).

Street art: mural painting

Mural paintings have a long tradition, significance and history in Indian Art. What makes them so unique is their natural relation to architecture and broad public significance. The deployment of the wide range of colours, designs, and themes in mural paintings can make a significant change in the sensation of spatial proportions.

“Serving simultaneously as collective mirror, canvas, testament and repository, this wall painting is ongoing, and it has not only given us a chance to connect to most of people in the locality, it has created an environment for communication, and established a public space for community interaction.”(Sreejata Roy)

Fearless Street Art project brings together communities to paint walls in the cities across India. Every city has a completely different cultural and social context that is relevant for that space. In order to understand the issues and the needs of the locals, Fearless organizes workshops mostly with local women, where they teach them how to draw and where they discuss with them about the subject matter that is relevant to their way of life. That is also the time where people can exchange ideas, so after this interaction they came to one affirmation which serves as a concept and only then it is ready to be placed upon the wall. Once the work is done and the painting with the positive affirmation placed on the wall it starts to communicate with the environment, slowly changing it by its mere presence. We can never be able to measure the impact of the wall painting and to be sure what kind of reactions it will provoke, however, its mere visibility, and the visibility of women with a strong message in particular, will be enough for the beginning in order to challenge the pre-existing categories in patriarchal society. The video for the project “Bonded not Bound” that was conducted in a slum Dharabi in Mumbai is an example par excellence of the work process of Collective.

What is the role of art in social activism?

Art is always a form of communication. Even when it is mere “ars gratia artis”, it communicates some emotions, moods and feelings. Art can also be a useful therapy and sanctuary. Namely, the art projects of Fearless Collective focus on building the trust among communities, on giving forgiveness and healing rather than on anger through compassionate dialogue. The purpose of art could also depend on the socio-cultural and socio-political context. What makes art an important factor in social activism is its main characteristic and that is creativity which can not only crash the boundaries but also go far beyond them. With Fearless Suleman employs her artistic talents to fight and struggle against gender equality injustice and oppression.

Social activists often make a cardinal mistake by projecting their own consciousness on the people they want to change instead of starting from consciousness of that people and that is the reason why many of them fail. Namely, India is home of largest population of illiterate adults in world – 287 million, amounting to 37% of the global total, nevertheless each region has developed its own style and tradition of storytelling in local languages. Therefore, the artistic activism of Suleman lies in the storytelling and creating a powerful personal contextual affirmation, which according to her is a medium of empathy for individual and social change. In workshops women share vulnerable and delicate stories and give their own interpretation of what it means to be Fearless and project that on the wall.

What landscape of fear is Fearless responding to?

The main idea of the collective is to send a powerful message to both women and men, which is that women should not be afraid to step out of the shadow and to take the place in this world, standing equally with the men. In Fearless projects the accent is given on the fighting the sexual objectification of women and the conquering fear of being visible in public space, fear of loitering, fear of being present in the night or fear of not being dressed in a proper way. The Fearless highlights the importance of accepting and loving oneself and of rediscovering femininity and women sexuality.

Here are some of the examples of the projects that Suleman conducted with the help of volunteers from artists and local communities that are worth mentioning.

Varanasi: “What we worship we shall become. Every woman is a goddess.”

The mural under the name “What we worship we shall become. Every woman is a goddess” was made in Varanasi. It was one of the first murals of the Suleman and the making of it left a big influence on her further work. The concept for it came when the artist was traveling through the Kumbh Mela in Allahabad. According to her story, one afternoon, she sat with naga babas and had a conversation with one of them about goddesses in India. She asked him why do men worship the goddesses on our walls, but rape the women in their homes, so his response was this: “When you (women) see your own divinity and strength, everybody else will follow”. Suleman interpreted this that instead of waiting for patriarchy to liberate women or to be worshipped, women have to make an effort to liberate themselves and see the strength of the goddess archetype within themselves. They have to reclaim their own right to spirituality.

The mural was painted on Assi ghat, near the place where girls sell candles to float. On the mural we can see a little girl and her cat looking up at durga (goddess of strength) and her tiger. The little girl says “What we worship, we shall become” and the goddess responds “Har Mahila Devi Hain”/ “Every Woman is a Goddess”. This mural proved that streets are actually a platform for public dialogue, and it showed the importance of the role of the street art to initiate that dialogue. Namely, as men and women passed by, stopping for a chai, conversations around women and sacredness would arouse.

Like in every patriarchal religion and culture, in Hinduism and Indian culture women were used to put down. However in India, there is an equally acceptance and understanding of strong feminine energy, the devi traditions. On the one side, women are told to cover up and by that I do not mean only physically covered. On the other side, there is goddesss Parvati being “digambara” which means ‘skyclad’ or topless so as to not block the flow of energy into her heart.

More to add, one spiritual stream tells them that all is ‘Maya’ and all things, feminine, earth-bound are illusion ,there is also the example of Annapurna Devi, who walks out on god Shiva when he says that she is illusion. And when she left him, the whole world starved until Shiva came back begging for forgiveness.

Delhi: ”Look at me with your heart, not your eyes”

The mural called “Look at me with your heart, not your eyes” in lower income area in Okhla, Delhi, was collaboration between SafeCity, Naaz Foundation and the Fearless Collective. In Delhi, as women walk they feel uncomfortable because of the gaze of men and they often report being stared at and harassed. Before painting the wall they organizers conducted a workshop with a group of 25 girls between 16 and 30. First, they had a long conversation with them, listening to the horrific stories of how they were finding the bodies of five year old girls in the fields and how they do not have the public sanitation. After the conversation, women drew portraits of themselves with eyes all around them, and had a discussion about being ‘Seen’ vs. being ‘Looked at’ in order to explore self a little bit and to see their qualities. Therefore, the concept for the wall came out of the affirmation “Buri Nazar Waale, Dil se Dekho, Aankho se Nahi” or “Look at me with your heart, not your eyes” and they filled the space in the wall with eyes, and wrote that they will not hide despite the gaze that cannot cease.

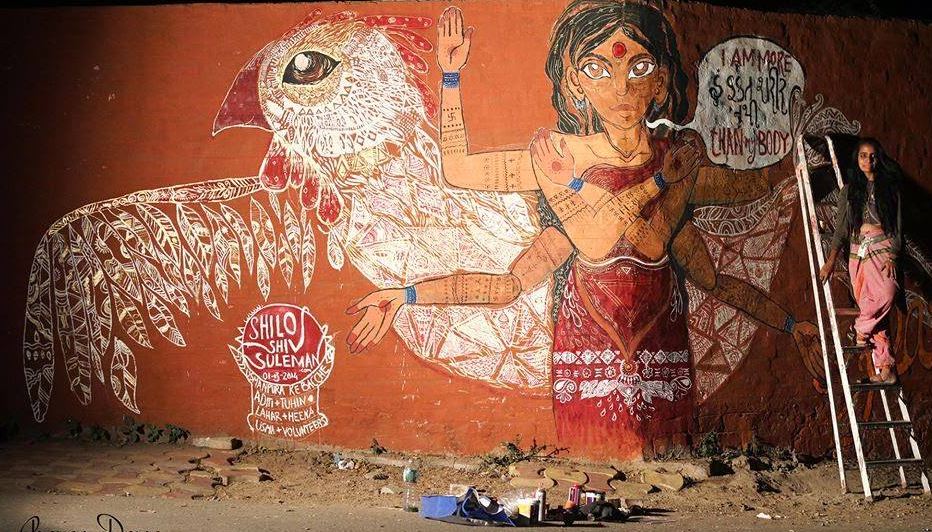

Ahmedabad: “I am more than my body”

The mural called “I am more than my body” was painted near Natrani with the help of local children and Fearless artists and friends, in an event organized on Woman’s day by Mallika Sarabhai, a famous dancer and an activist from Ahmedabad. After the discussion the concept came out of the affirmation: “I am more than my body”. It was inspired by the story of patron goddess of Gujarat- Bahuchara Mata, who was walking in the desert when she was followed by a group of men who started to attack her and grab her body. She cut off both breasts and handed it to them saying:”Here, you want these? Take them.” The gods who were watching this made her a goddess and protector of women, as well as devi of the transgender community in India. Behind her there is a big white bird as a sign that when one steps ‘beyond gender’, one is free.

Chennai: ”I am my own hero”

The mural called “I am my own hero” is made in the train station in Chennai in 2015. It depicts the golden couple of old Tamil cinema, Sivaji and Padmini, who emerge out of jasmine flowers. Silvaji is a true warrior, and like in a movie, he wants to protect Padmini, to become her savior and to take her into his arms. However, nowadays, Padmini, does not need his protection anymore, because she is not care for herself. Therefore, she gently pushes him back and assures him: “I am my own hero”. Like in most old love stories, there are archetypes that dominate, and Indian cinema is no exception. There must be a hero, a virgin, and a scene where he must save her from other men who threat to take her honor). Usually, the love story finds its resolution in a strange dynamic between the questions of possession and consent. The mural “I am my own hero” was collaboration for Street Art Chennai between painter M.P.Dakshna and Shilo Shiv Suleman of the Fearless Collective. The concept came out of the workshop on Gender and Consent in Tamil cinema, that they organized and where residents of Chennai were making posters in order to challenge existing iconic cinematic imagery and to retell the stories, recast the roles, and reclaim the streets.

Transcultural aspects across India and Pakistan

India is not a unique case in South East Asia. “There’s the shared experience of the peculiarities of South Asian notions of izzat and honor which mean that we need few explanations and our experiences in India and Pakistan are legible to each other without footnotes and citations. What began as a mutual admiration society has grown into a collaborative endeavor” (Phadke, The Hindu, 2015). Inspired by the murals of Fearless Collective, the transgender rights group Wajood wanted to call attention to the fight for trans rights in Rawalpindi, so they invited Suleman to paint with them. They spend some time within khwajasira community and had a discussion about how they perceive themselves. The mural depicts the leader of the activist group, Babli Malik, riding a motorcycle which is exhaling flowers, with the words ‘Hum hain khuda-e-takhleeq’ which translates to ‘I am a creation of God., an absolute affirmation and reclamation of one’s right to dignity. The most striking thing about this mural is that is placed right next to the place where men wash and repair their vehicles, and in such way remind us of Sreejata Roy’s wall painting of women in the streets of Delhi.

Riwalpindi: “I am a creation of God”

Conclusion

These little steps that women and Fearless Collective make are so powerful, and they could even mobilize the whole society, it is still a growing project and they do not know where this is going to get them to, but it is going to give them at least the sense of freedom and far more confidence in ability to change the society. Furthermore, apart from the beautification of the public spaces, and from bringing the art on the street, Fearless tacitly approached those women, who are poor, often not educated enough and who perhaps are not even conscious of their own rights and showed them that only if women stand together and occupy the public space together no matter what caste they belong to, they can overcome their fears of being visible in the public and harassed in any way. Likewise, Fearless has shaken the pillars of feudal patriarchal and caste system as well as the religious fundamentalism by using the examples mythology that are somehow forgotten or not praised enough especially by men.

Although in most cases Fearless does not directly mobilize and engage men and boys to address the issue of gender-based violence, at least it produces some feeling in them that the change of viewing women as a human being that is equal to them is more than necessary. Still, if we want to challenge patriarchy and work towards gender equality we must include more men to understand their privileged status in patriarchal system and the fact that what are women fighting for is actually part of fundamental human rights of all people.

Literature